She describes this work as “a means of survival,” but survival here seems to be a messy, disorienting, deeply experimental reckoning with life, history, and intergenerational trauma. She commits herself to a psychiatric hospital and receives diagnoses of PTSD and bipolar II, but inside she begins to work on much of what comprises Heart Berries, writing down memories, observations, and intimate epistolary chapters addressed to Casey. Then she falls hard for a fellow writer, Casey the other men fade, and it seems as though things are improving.īut, Mailhot writes, “I knew I was not well”: she harms herself repeatedly, acts impulsively, lashes out violently, is too thin. That’s when I started to illustrate my story and when it became a means of survival.” With her baby, Mailhot moves from the familiarity of her mountains to what she describes as “an infinite and flat brown” - one that nevertheless holds possibility there, she seeks education, writing classes, college, tries to soothe her hunger with the gifts of men. I used a check and some cash I saved for a ticket away-and knew I would arrive with a deficit. “I left my home,” she writes, “because welfare made me choose between necessities. We ruined each other.” When her mother dies and Mailhot loses custody of her first child, Isadore, just as she is delivering her second child, she leaves her reservation in grief and hunger. She has already endured a childhood of poverty, neglect, and abuse now ending is a teenage marriage of which she says simply, “Despair isn’t a conduit for love. In keeping with a kind of poetic efficiency that marks Mailhot’s work, the book opens right into a rupture. All the tensions Mailhot manages here - between what she has lived and what she makes of it, between the ugliness of experience and the graceful, spare prose she uses to convey it, and between how people are with how they might have been - make Heart Berries a standout in the genre.

In these pages, the harrowing truth of her young life is balanced by a voice as even and precisely controlled as poetry. I can’t turn it into Salish art.” Yet Mailhot, a member of the Seabird Island Band and the daughter of a poet-activist and a Salish artist, has written one of the most simply beautiful memoirs of inherited trauma, mental illness, motherhood, and love that I’ve read in recent memory.

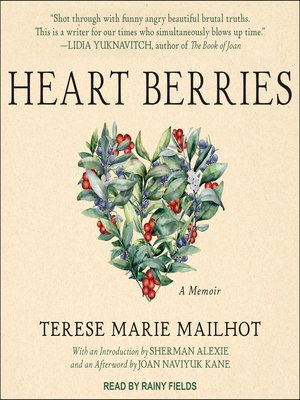

“The truth of this story,” she writes, “is a detailed thing, when I’d prefer it be a symbol or a poem - fewer words, and more striking images to imbue all our things. In her debut memoir, Heart Berries (Counterpoint, February 2018), Terese Marie Mailhot reflects on the challenges of negotiating the gap between the ugly truth and the art she hopes to make out of it.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)